The Other Greedy Jobs

Some jobs require a breadwinner/homemaker division of labor and that cannot be changed

The brilliant economist Claudia Goldin published a book called Career and Family in 2021 that has been deeply influential in my own personal life — and more importantly, in the wider world. Goldin won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics. Career and Family summarizes an important line of research that has been a through-line of her career. One of the central premises of the book is that many elite jobs in the twenty-first century are “greedy jobs,” meaning that those who put significantly more work into their careers also receive significantly more compensation. This leads, Goldin correctly argues, to fewer women in the high-paying full-time workforce, because taking care of young children is hard to square with “greedy jobs.” The solution? Goldin argues (in part) for more flexible jobs. According to a great New York Times essay on the topic, when it comes to creating a more equitable workforce,

…[t]he most effective way to do that, Ms. Goldin’s research has found, is for employers to give workers more predictable hours and flexibility on where and when work gets done. One way that happens is when it becomes easier for workers to substitute for one another.

In other words, the more employers can turn high-paying jobs into those with predictable hours and flexible locations, the more mothers with young children can hold down such jobs, leading to a decrease in the gender pay gap.

While I am wholeheartedly supportive of efforts to make jobs more flexible and predictable, Goldin is largely focused on elite jobs available to white-collar workers. Blue collar jobs with serious physical and travel demands are largely left out of discussion. I think of these as “the other greedy jobs,” and believe their existence has profound implications for how we should think about the “gender pay gap” and our goals for women’s workforce participation.

White Collar Greedy Jobs

Let’s begin with Goldin’s insights into “greedy jobs,”which include (per the NYT) “finance, law and consulting.” The differential pay at the top of the pay scale for these white-collar jobs are part of what the NYT calls “the nation’s embrace of a winner-take-all economy.” Consider two lawyers who start at a large law firm. One young attorney sacrifices nights, weekends, and vacations to work, and bills significantly more hours than her peers. This hardworking attorney is likely to be rewarded with the gold ring of law firm partnership, meaning potentially millions of dollars in compensation. One report notes that some “BigLaw” firms paid up to $20 million in compensation per partner last year! The other attorney decides to aim for a better work-life balance. She works hard at her job, but also is careful to preserve many nights and weekends to spend with her family. This leads her to achieve an “Of Counsel” role, which is a highly-ranked position in a law firm, but certainly not as lucrative as partnership. Estimates of the compensation for such positions are hard to come by, but probably top off in the high hundreds of thousands of dollars, not in the many millions. Thus, the difference in salary between an “Of Counsel” position and a partnership position is measured by orders of magnitude. This is not a small pay differential.

Goldin notes that families respond to these pay incentives rationally. Specifically, for a family with young children, the couple often engages in specialization. She writes “primary caregiving is time consuming” so one parent reasonably decides that “[t]o be more available to their families, they must be less available to their employers and clients.” This frees up the other, working parent, to pursue the “greedy job” with its very significant financial upsides. Put another way, by engaging in this sort of specialization, a couple can end up making more money together with one parent having a flexible job and the other a “greedy job,” than they would with both parents working flexible jobs.

Goldin suggests that the presence of “greedy jobs” is undesirable in part because it contributes to gender inequity between women and men’s career attainment. She suggests that employers “have to make flexible positions more abundant and more productive” in order to ensure women can fulfill both caregiving and work roles. I am all for this: the presence of remote work and flexible jobs is a boon for primary caregivers. However, flexible jobs will always remain only a partial solution to this issue because many jobs are simply not amenable to caregiving. These include a number of well-paying blue collar jobs.

Blue Collar Greedy Jobs

While Goldin focuses primarily on high-paying elite jobs (lawyers, doctors, etc.) there are many middle- and working-class jobs that simply cannot be made amenable to caregiving parents generally and pregnant mothers specifically because they have such intense physical and travel demands. Put another way, either the job requires significant time away from family, or they are so physically demanding that they are difficult to do while pregnant (or both). Yet, these blue-collar “greedy jobs” usually pay comparatively well, and so they can be highly desirable for those with the skills and flexibility to do them.

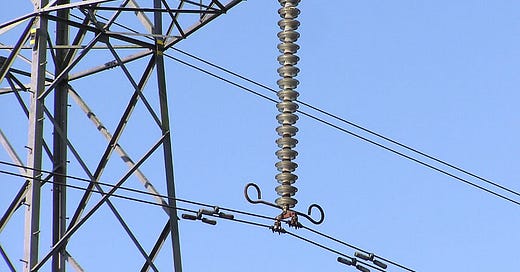

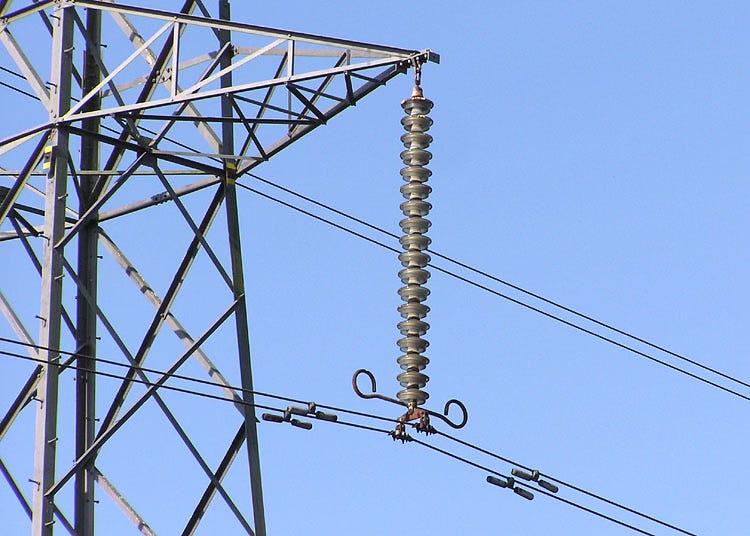

For example, I once talked to a mom married to a traveling lineman. Traveling linemen respond to serious issues with the electrical grid. When a tornado knocks down power lines throughout the Midwest, or a major snowstorm brings down trees and power lines in New England, traveling linemen respond to get the grid back up and running. This is obviously a vital job, and it pays a premium over many other jobs in the trades. His travel was both unpredictable and extensive, however, and so this couple decided it didn’t make sense for her to work while their kids were young. Many other well-paying jobs that are primarily held by middle- or working-class men are similarly inflexible in terms of “work/life” balance issues. Trucking, working on an offshore oil rig, workers on a new interstate natural gas pipeline, traveling welders, merchant mariners … there’s a long list of jobs where if one spouse is doing them, the other spouse is going to be frequently left alone to handle home and hearth. Additionally, the physically intense nature of many of these jobs means the spouse at home is probably going to be mom … not dad. (E.g., most women would not sign up to be pregnant or postpartum on an offshore oil rig.)

Probably the archetypal example of a “greedy job” that demands physical strength and significant travel is the military. If your spouse is in the special forces, you must be prepared for him (or occasionally her) vanishing for weeks or months at a time with no warning. For obvious reasons, pregnancy and special forces deployment are not compatible (even to enter special forces training you usually need to show a negative pregnancy test). If the military spouse has a more run-of-the mill job, military families still face long deployments and move frequently from base to base. For a family with small kids around, this unpredictability combined with frequent moves makes it difficult for the non-military spouse to work.

As discussed above, Goldin argues that many white-collar “greedy jobs” can be made less greedy. For example, as the New York Times points out,

Obstetricians, for instance, used to be on call when patients went into labor. Now it’s much more common for them to work eight-hour shifts in a hospital — and many more women do the job.

The transition to shift work is good for the OBs. I’m not sure how politically correct it is to raise this issue, but: query whether it is better for patients? When I delivered each of my four children, it was stressful to arrive at the hospital unsure about who would deliver the baby. Twice the delivering doctor was someone I had never met! Additionally, despite relatively short labors, three times my labor crossed a shift change and so I began laboring with one doctor, but was delivered by another; meaning meeting and discussing issues twice (or, let’s be real, not discussing anything with the second doctor because I was about to give birth).

Putting aside quality issues, many blue-collar “greedy jobs” cannot be made flexible in the same way as certain “greedy” white-collar jobs. A linemen who travels across the country in response to the destruction wrecked by a category five hurricane simply is not going to be home for dinner. We cannot make special forces jobs less intense for “work-life balance” reasons: those jobs are critical for national security. Long-haul truckers and merchant mariners, by definition, must spend days, weeks, or months on the road or sea. Many families in which one spouse holds such a job reasonably respond by setting up things so that the other spouse is at home with the kids.1

Implications

What should it mean for society that there are a number of vital jobs that put a lot of pressure on families to have a homemaker/breadwinner division of labor … and moreover the homemaker is usually mom?

I think the right conclusion is : these are useful jobs, they cannot be made more flexible, and therefore our society should support the families that make them possible.

There is a sense among many policymakers that two-working parent families are more economically productive, and so deserving of greater support. An article published by Forbes last month is typical of this line of thinking:

[I]f women’s workforce participation in the U.S. matched the highest levels seen in peer nations (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the U.K.), 7 million more women could join the U.S. workforce, fueling up to 4.2% in economic growth. The continued decline in mothers’ workforce participation threatens this opportunity and signals long-term consequences for GDP growth, family economic mobility and national competitiveness.

While I wholeheartedly support the many impressive career attainments of women during the past fifty years, I think the line of thinking laid out by Forbes is too simplistic for many reasons. One of them … the entire point of this essay … is that some important jobs simply cannot be easily done without a breadwinner/homemaker division of labor! A just society would take this problem seriously. So would smart policymakers: many of these blue-collar “greedy jobs” are facing critical shortages. Linemen, for example, are in very short supply, and that shortage is only expected to grow as older workers retire.

What can be done to support these families? I think the first priority should be protecting the homemakers within them. These homemakers are not covered by the protections offered to someone working full-time in the formal work force. They often face significant penalties at retirement age, encounter serious challenges if the breadwinner dies, and deal with a host of other unique challenges too numerous to fully enumerate in this post. As I have written about elsewhere, our healthcare, retirement, and social safety net systems are not well suited to cover stay-at-home parents. To take just one example: a married homemaker who becomes disabled is not going to be covered by a workplace disability plan, will not be covered by Social Security Disability Insurance if she has been out of the paid workforce for a long time, and will likely means-test (based on family assets) out of the “SSI,” the disability coverage available to the very poor.

Second, we should rethink our emphasis on eliminating the gender pay gap, increasing women’s workforce participation as much as possible, and achieving a perfect 50-50 division of labor between mothers and fathers. Often, those focused on these issues push for government-subsidized external childcare. Christopher Lasch, the historian and cultural commentator, wrote in a famous essay, The Sexual Division of Labor, that “demand for state-supported programs of day care discriminates against parents who choose to raise their own children and forces everyone to conform to the dominant pattern.” I have some quibbles with this phrasing. First, I certainly think full-time working parents “raise their own children,” regardless of their use of external childcare. Second, it is overstated to claim that providing state-funded daycare “forces everyone” to “conform” to the two-working parent model.

I do think, however, that subsidizing daycare but failing to support stay-at-home parents puts a thumb on the scale in favor of the former, especially if the latter are not eligible to use the subsidized care. For example, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit does not allow homemaker parents to use it, even if they have external childcare needs. Consider the (hypothetical) example of a wife of a lineman with three kids, one of whom has a serious medical condition and needs physical therapy 3x per week. Even if it would help her considerably to hire a babysitter to watch her other children while she takes the medically-complex child to his therapies, she is not eligible to claim that tax credit.

Ultimately, the existence of these vitally important, yet inflexible jobs should cause us to be skeptical that we will ever achieve a perfect 50-50 division of labor between mothers and fathers. Some work doesn’t lend itself to that outcome. Likewise, trying to zero out the gender pay gap seems quixotic, given these constraints. To be sure, we should still take workplace discrimination seriously, and ensure women who want to pursue full-time paid work are able to do so fairly. But the key question should be: are families happy with their work arrangements? If they are, good policy should not aim to push homemakers to enter the paid workforce. Rather, it should try to ensure they are protected from the risks they run by staying outside the formal labor market. We need people to work “the other greedy jobs,” and we should protect the spouses at home who make that difficult work possible.

This is especially true because the kind of flexibility available to elite, white-collar caregiving parents is also not available to working-class moms. A lawyer can find a flexible job that allows telecommuting. A mom who works at a manufacturing plant is going to have a much harder time getting the workplace flexibility needed to take care of a bunch of little kids if her husband is at sea for months on a fishing vessel. She’ll probably drop out of the workforce instead. This kind of flexibility is something that can be tackled by employers, unlike the kinds of blue collar greedy jobs I discuss above, and it would be good to incentivize those changes. But either way, if dad is gone for many months of the year, a family with five kids is probably going to want mom at home, regardless of how many flexible jobs are available for her to take.

Fantastic and thought provoking essay essay. Two thoughts come to mind: Economics aside, I don't know why normal people are supportive of programs meant to make it easier to have two-income households, ~instead~ of programs that would make it easier to live on one income. I suspect people just can't fathom the idea of one income any more — even though everyone seems to hate their jobs. imo the target or goal should be a world where one income is viable, even if we're not at currently there.

The other thought is that Goldin's work seems quite interesting. But the prioritization of the managerial class completely omits an alternative elite pathway, which is means-of-production ownership (ownership of businesses, people who own real estate, etc etc etc). I'm someone on the managerial class ladder, but the more time that goes by the more I'm convinced that is the inferior pathway.

An incredible quote from that Forbes article! Sure, 7 more million women *could* enter the workforce, increasing GDP...but at what cost? Do those women even have a desire to enter the workforce? What would the (non-monetary) costs be for them to work?